During the 18th century watchmakers in England and France continued to produce the largest quantity and the best quality watches. In each of these countries their distinctive style was further developed until the end of the century where the exchange between the two countries increased and gave rise to a more uniform style of big, flat watches.

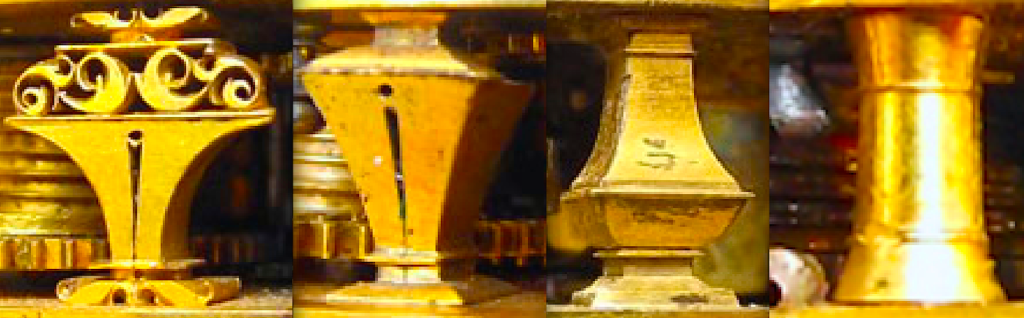

Both countries followed the same change of pillar style, getting away from the tulip and Egyptian type towards the square baluster style, which started to get shorter, thinner and rounder towards the end of the 18th century, especially due to the effort of making smaller and flatter watches. The use of pillars got obsolete, when newer movement configurations took over using separate bridges omitting the back plate, a system invented by French watchmaker Jean – Antoine Lépine and refined by Abraham – Louis Breguet.

In England the watches kept the single footed cock, but the D- shape of the cock-foot seen at the end of the 17th century was retained only until about 1710. Starting from then, the foot got narrower and the diameter of the cock itself diminished. An exception were the few important and big watches built around John Harrison’s ‘H4’ and Thomas Mudge’s chronometers which had two footed cocks due to their large size, resembling the Dutch style (B). The English retained their rear winding system throughout, but added consequently a dust cap for protection as soon as the cylinder escapement was introduced. Silver and gold as material for dials got replaced by enamelled copper. One of the most important English contributions to gaining precision in timekeeping in the early 18th century was made by George Graham, who perfected the cylinder escapement. He used it throughout starting from 1725/6. Thanks to his refinements watches could be of thinner construction and of smaller size.

The cases remained rather plain, with occasional engravings such as coat of arms at the beginning of the century. This changed towards 1740, where quite elaborate gold and silver cases with repoussé work appeared. The English preferred their paired cased system, whereas the French mostly continued to case their movement in a single, consular case.

During the 1750s Thomas Mudge developed the lever escapement and in parallel the Longitude problem was tackled by several watchmakers, inspiring John Harrison to develop one of the most famed watches in history: the ‘H4’. Other watchmakers simplified Harrison’s concepts creating ‘Chronometer’ watches, the most precise pocket sized timekeepers of their time. John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw disputing over the privileges of perfecting escapes and compensation balances and building marine chronometers, some of which accompanied the most important geographical expeditions of the 18th century.