Description: Multi cocked, late Lépine-type, gilt brass duplex movement (40mm diameter), compensation balance, Steel spiral balance spring. Adrien Philippe’s patent stem setting keyless work. Original stem and crown. Original enamelled dial with asymmetrical sunk seconds between 4 and 5. Signed ‘Vulliamy Pall Mall’. (A)

Provenance: Ex private collection Vaudrey Mercer (UK)

Published: Clocks Magazine, June 1984

Additional Info:

The sunken disk is separately built, enamelled and then inserted into a hole made into the dial. This ‘English’ way of having a sunken subdial is more complex and delicate to manufacture then the ‘French’ protocol of just grinding the sunken part into the dial, as Breguet had it made. (A)

This type of movement with the unusual keyless setting with wolf’s tooth winding after a patent by Adrien Philippe was exclusively distributed by Patek & Co. at that time. Vulliamy probably had heard from the gold medal earned for this invention at the 1844 World fair in Paris and introduced the system in England. Vulliamy must have ordered it directly from Patek, that might explain the high production number, unusual for the Vulliamy firm. If coming from Patek the production number could be from them, and this would date the movement to around 1853 (A). Another hint towards an imported movement is the lack of signature on the original dial, which mostly indicates, that the watch is not entirely made in the respective workshop.

David Penney believes that this movement is the earliest known keyless English movement of this type, No. 4536 belonging to Queen Victoria not having been made in England, see below (A).

Jean Adrien Philippe (1815 – 5. 1. 1894)

Born in La Bazoche Goüet (Eure-et-Loir), he was a French horologist and cofounder of Patek Philippe & Co. of Geneva.

In 1842 Adrien Philippe invented a mechanism for watches which allowed them to be wound and set by means of a crown rather than a key. At the French Industrial Exposition of 1844 (World’s Fair) Adrien Philippe first met Antoine Norbert de Patek and a year later became head watchmaker at Patek & Co. in Geneva under an agreement that entitled him to one-third of all company profits.

Adrien Philippe proved to be very capable at his craft and a product innovator whose value to the firm was such that by 1851 he was made a full partner and the firm began operating as Patek Philippe & Co. In 1863 he published a book in Geneva and Paris on the workings of pocket watches titled ‘Les montres sans clef’.

His partner Antoine Norbert de Patek died in 1877 and in 1891 the 76-year-old Adrien Philippe handed over the day-to-day management of the business to his son Joseph Emile Philippe and Francois Antoine Conty.

Jean Adrien Philippe died in 1894 and was buried in St-Georges Cemetery in Geneva.

The company Patek Phillipe exists to this date and is still located in Geneva. A part of their famed watch manufacture, they also have a very nice watch museum where one can admire historic pieces of their production.

Adrien Philippe’s Keyless Winding and Setting System

Until the mid-19th century, pocket watches were wound and set with a key fitted into holes either in the case or dial. Through these holes, dirt could penetrate the movements or the keys were lost. For nearly 250 years, watchmakers had not found a practical solution to these problems.

The first known keyless movement (wound by pressing the stem) is by John Arnold and dates from 1766 (see short description above). During the early 19th century John Roger Arnold (Prest keyless winding system, from about 1810) and others already mounted keyless movements but in the early 1840s, Adrien Philippe introduced special features no other watchmaker could offer, thus stimulating the newly created firm’s business. His invention was initially greeted with skepticism by fellow watchmakers. The breakthrough finally came at the Paris Exhibition of 1844 in form of a gold medal for his very slim stem-wound watches displayed and, perhaps even more importantly, making the acquaintance of Antoine Norbert de Patek who immediately recognised Adrien Philippe’s visionary system as much more than just another technical gimmick. Patek already had several years of experience with the sale of stem-wound watches, produced by Patek & Czapek with Louis Audemars’ system since 1839.

Adrien Philippe’s invention of the modern winding and setting stem and crown (pull out to set, push in to wind), French patent No. 1317 of 1845, was more than a clever mechanism. It changed the nature of watches and allowed the evolution from the keyless watch to today’s waterproof wristwatch.

Philippe continued the development and perfection of crown and stem winding and setting for almost 20 years. By the time he filed his final patent on the matter in France in 1861 (as the only official patent office was in Paris at that time), the first had already expired and his idea was in current use.

Adrien Philippe had wished that his invention would be ‘applicable to all types of watches’ and indeed, his system is used to this day in timepieces that he would probably never have imagined: self-winding and ultra-thin wristwatches, quartz watches and diver’s watches.

Queen Victoria’s Watches

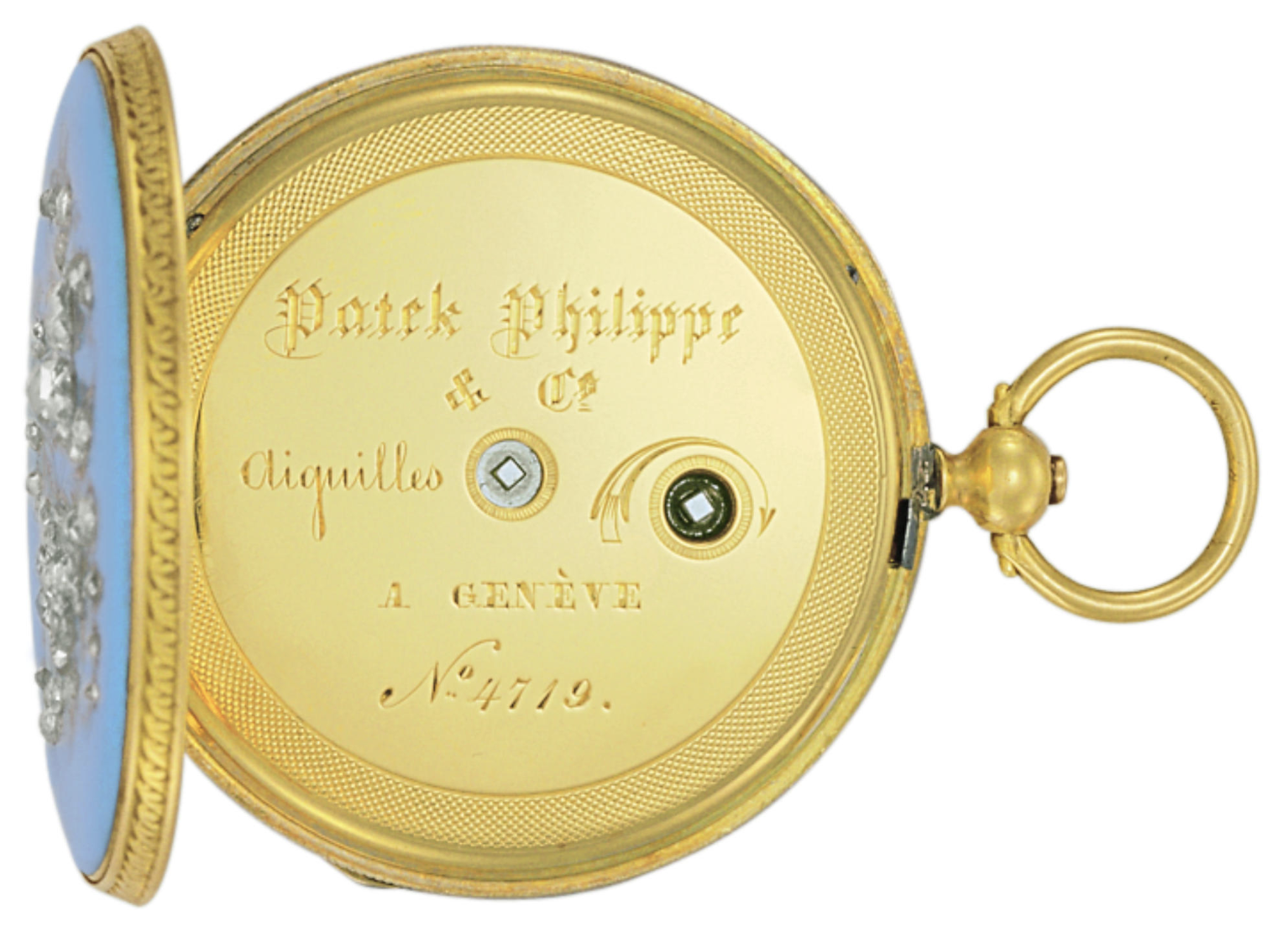

Queen Victoria first discovered the brand when they presented at the London Universal Exhibition in 1851. Her watch of choice was a light blue pendant watch, No. 4719. The timepiece features a flower bouquet set with rose-cut diamonds on a sky-blue enamel ground. It comes equipped with a yellow gold case, white enamel dial, painted Roman numeral hour markers, and blued steel Breguet hands (1).

At the Great Exhibition, Queen Victoria was also presented with a second pendant watch of a similar fashion. No. 4536 displayed a bouquet of rose-cut, diamond-set roses set on a lapis blue enamel ground backdrop. In addition to the signature on the case, this particular model also has an engraving of the words, “INVENTION BRÉVETÉE.” This marking indicates that the watch employs Jean Adrien Philippe’s stem-winding system. Soon after, Queen Victoria appointed Patek Philippe as her royal watchmaker. Her appreciation for these timepieces helped put the brand on the map, especially in countries who did not previously have an association with the manufacturer (1).

It is conceivable that Vuillamy wanted to ride on the success of Patek Philippe and the fact that they were appointed as royal watchmakers to the British crown and thus ordered a few movements from them, which were finished in London in English style.

Ref.: