The measurement of longitude was a problem that came into focus as people began making transoceanic voyages. Determining latitude was relatively easy in that it could be found from the altitude of the sun at noon with the aid of a table giving the sun’s declination for the day. For longitude, early ocean navigators had to rely on dead reckoning. This was inaccurate on long voyages out of sight of land and these voyages sometimes ended in tragedy. Finding an adequate solution to determining longitude was of paramount importance.

Many ideas were proposed for how to determine longitude during a sea voyage. Earlier methods attempted to compare local time with the known time at a given place, such as Greenwich or Paris, based on a simple theory that had been first proposed by Gemma Frisius (1508 – 1555, Mathematician, The Netherlands). The methods relied on astronomical observations that were themselves reliant on the predictable nature of the motion of different heavenly bodies. Such methods were problematic because of the difficulty in accurately estimating the time at the given place.

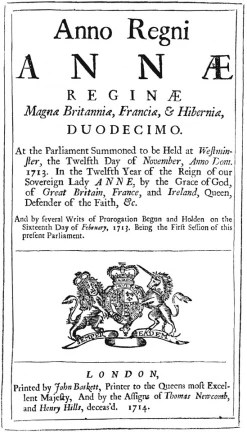

The Longitude Prize was a reward of £ 20,000 offered by the British government for a simple and practical method for the precise determination of a ship’s longitude. After the Scilly naval disaster of 1707 which claimed the lives of nearly 2,000 sailors, Queen Anne refocused on the problem. The prize, established through an Act of Parliament (the Longitude Act) in July 1714, was administered by the Board of Longitude.

This was by no means the first such prize to be offered. Philip II of Spain offered a prize in 1567, Philip III in 1598 offered 6,000 ducats and a pension, whilst the States-General of the Netherlands offered 10,000 florins. But these large prizes were never won, though several people were awarded smaller sums to continue their research.

John Harrison set out to solve the Longitude problem directly, by producing a reliable clock that could keep the time of a given place. His difficulty was in producing a clock which was not affected by variations in temperature, pressure or humidity, remained accurate over long time intervals, resisted corrosion in salty air, and was able to function on board of a constantly-moving ship. Many scientists, including Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens, doubted that such a clock could ever be built and favoured other methods for reckoning longitude, such as the method of lunar distances. Huygens ran trials using both a pendulum and a spiral balance spring clock as methods of determining longitude, with both types producing inconsistent results. Newton observed that:

“a good watch may serve to keep a reckoning at sea for some days and to know the time of a celestial observation; and for this end a good Jewel may suffice till a better sort of watch can be found out. But when longitude at sea is lost, it cannot be found again by any watch”.