Abraham – Louis Breguet (10.01.1747 – 17.09.1823) was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland to Jonas – Louis Breguet and Suzanne – Marguerite Bollein. The young Breguet soon astonished his master with his aptitude and intelligence, and to further his education he took evening classes in mathematics at the Collège Mazarin (Paris) under Abbé Marie, who became a friend and mentor to the young watchmaker. Breguet was allowed to marry in 1775 after finishing his apprenticeship. He and his bride, Cécile Marie – Louise L’Huillier, set up their home and the Breguet watchmaking company; its first known address was at ’51 Quai de l’Horloge’ in ‘Île de la Cité’ in Paris. Unfortunately the house number is no longer there, as at some point the street numbers have been completely changed.

As Breguet’s fame gradually increased he became friendly with revolutionary leader Jean – Paul Marat, who also hailed from Neuchâtel. Breguet invented or perfected innovative escapements, including the final development of the tourbillon, the overcoil (an improvement of the balance spring with a raised outer coil, invented by John Arnold) and perfected automatic winding mechanisms. Within ten years Breguet had commissions from the aristocratic families of France and even the French queen, Marie – Antoinette. Cécile died in 1780.

Breguet as watch manufacturer and retailer

Abraham – Louis Breguet is well known for his complex watches and the excellent finishing of all his pieces. While Breguet himself concentrated on the development of new features and inventions, his workshop focused on translating the ideas of the master into works of art. To manufacture watches was very laborious. It took about 2 years to build a watch in Breguet’s workshop, at the beginning. With optimisations and more workforce this could be reduced to 15 to 18 months in later years.

As his developmental work and the in house building of watches needed to be financed, especially in the first 5 years of existence and during politically unstable periods, it was impossible for the Breguet workshop to make all the watches they were selling themselves. Some watches were finished from prefabricated ‘ébauches’ (raw movements) other watches were bought for resale completely prefabricated from trusted manufacturers such as Decombaz in Geneva and Houriet in Le Locle. Starting from 1794 Breguet also bought prefabricated watches made in and around Besançon, where during his exile in Switzerland he co-founded a watchmaking school.

The gain margin varied enormously. While for the simpler watches the gain was between 33% and 35%, for the more complex watches Breguet calculated up to 65% gain.

The early years: 1775 – 1780

While the master and the workshop specialists were working on exceptional pieces (especially the ‘perpetuelles’ at that time), the income was dependent on the sale of simpler watches, with verge escapements for example, which were bought as complete watches, engraved with Breguet’s name, sometimes finished but in no way made in his workshop. These watches do retain the exceptional quality for which the Breguet workshop is known and admired for, but some minute details will identify them as ‘retail pieces’.

Only the watches completely made in the Breguet workshops, or specifically made for Breguet have the ‘raw movement’ number (stamped on the dial plate) which is identical to the production number. The mentioned retail pieces either do not have production numbers at all (pieces before 1782) or they were attributed a production number when sold later (as No. 149bis). In latter pieces the production number does not correspond to the stamped raw movement number. In exceptional cases the raw movement number ist taken and converted to the production number, as happened with Breguet’s No. 242.

Most of these early retail pieces were made and sold before the systematic introduction of a ledger, which was around 1787. Others do not enter the ledgers, as they are not considered ‘in house pieces’. Alphonse Chapiro has developed on these retail pieces in a bulletin for A.N.C.A.H.A (No. 36, in 1983). Most of these simple retail watches do not bear Breguet’s signature on their contemporary dial. A habit which will continue to be applied in most pieces of the ‘Etablissement Mixte’ in later years. Some early pieces which would have had an unsigned enamelled copper dial, have been updated later with a guilloched silver dial which then was engraved with the firm’s name.

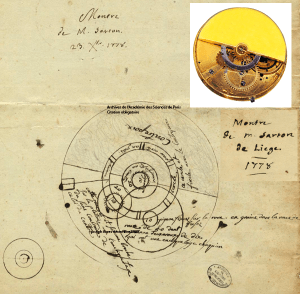

Breguet met Abraham – Louis Perrelet (supposedly the inventor of the automatic, self winding mechanism (now contested and invention of the self-winding system is attributed to the Belgian Hubert Sarton who deposited a drawing to the ‘Académie Royale des Sciences’ in Paris, the 16.12.1778), later improved by Breguet and named ‘perpetuelle’) in Switzerland and he became a Master Clockmaker in 1784. In 1787 Breguet established a partnership with Xavier Gide and latter’s brother, which lasted only until 1791. In the early 1780s the Duke of Orléans went to England and met John Arnold, then Europe’s leading watch and clockmaker. The Duke showed Arnold a clock made by Breguet, who was so impressed that he immediately travelled to Paris and asked Breguet to accept his son as an apprentice.

‘La Terreur’ in France and Breguet’s exile to Le Locle: 1793 – 1795

In 1793 Jean – Paul Marat discovered that Breguet was marked for the guillotine, possibly because of his friendship with Abbé Marie (and/or his association with the royal court); in return for his own earlier rescue by Breguet, Marat arranged for a safe-pass that enabled Breguet to escape to Switzerland the 12th of August 1793, from where he travelled to England. This same year the 13th of July 1793, Marat was stabbed in his bath tub by Charlotte Corday from Caen. Before he died he cried to his wife:

“Aidez-moi, ma chère amie!” (“Help me, my dear friend!”).

Breguet’s journey to Switzerland included a short visit in Ferney and Geneva (to visit Decombaz)and a longer stay in the region of Neuchâtel and Le Locle. Afterwards he remained in London for some time, during which he worked for King George III.

The tumultuous period between 1793 and 1795, during Breguet’s exile in Switzerland coincided with the forced moving of the Breguet workshop in Paris. These events mark a crisis in sales and show a new rise in the sale of pre-made retail pieces from his workshop. The founding of the ‘Horologerie Nationale’ in Besançon in late 1793 by Breguet’s relative Laurent Mégevand and the removal of taxes on silver and gold cases in the region of ‘Franche – Comté’ of which Besançon is the capital, starting from 1794, opened a new source for acquiring complete, simple watches of better quality than the ones made in Geneva, and cheaper than the ones made in Paris. In the national bulletin of 1803 (Bulletin de la Societé d’encouragement pour l’industrie nationale, Vol. 2, 1803, p. 253), Breguet is mentioned as important contributor for the talents and the activity of the newly founded firm in Besançon. The watchmaker François Robert, also from Le Locle as Megévant (and Breguet from 1794 to 1795), working for the ‘Horologerie Nationale’ in Besançon, received a silver medal for his work in 1802, where the consistent and excellent quality of his pieces is mentioned. It is highly probable, that Breguet’s pieces sourced from Besançon were made by Robert. Mid 1794 Breguet has even been asked by Mégevand to preside the ‘Horlogerie Nationale’ in Besançon, an honour which Breguet refused, as he was intentioned to regain his struggling workshop in Paris as soon as possible for concentrating in putting into production the many new ideas developed during his exile.

The low number of such pieces for Breguet which survived in original state are mounted in cases bearing the (tax exempting) hallmarks for Besançon between 1794 and 1809. As Le Locle (in the Swiss canton of Neuchatêl), where friends and suppliers of Breguet were located, had been repeatedly refused by the French government to take advantage of the exempt of taxes on silver and gold cases introduced in the region of Franche-Comté, one can be fairly sure, that these pieces were completely manufactured in Besançon and not in the neighbouring Swiss cantons.

Moreover, the complex movements and complete watches made for Breguet by his friend Houriet in Le Locle were shipped to Paris by means of the transport firms of Besançon, meaning that during the delivery of complex pieces from Le Locle to Paris, the transport vehicles had to pass by Besançon, allowing to gather orders for less complex watches and parts made in Besançon and which then were transported to Paris with the same shipment. Even today, all fastest land connections from Le Locle to Paris mandatorily pass by Besançon.

Of course for these ‘retail pieces’ as for other early pieces, the provenance can not as easily be traced, as if the watches were recorded in the firms ledgers. Most extensive research (mostly lasting several years) is needed for an attribution of such pieces to the Breguet firm. However, already Alphonse Chapiro and George Daniels new, that the ledgers, although of utmost importance, represent a limited source to englobe all of Breguet’s engineering -and in this context- marketing and salesman genius. Hence, especially for these ‘retail pieces’ following principles by George Daniels apply:

“To supplement his business during the development and making of perpentuelles Breguet sold the more common simple and repeating watches of the day. (sic) He maintained the most cordial business connections with Swiss makers (and we know now, also with the Lépine and Hessen workshops in Paris and the ‘Horlogerie Nationale’ in Besançon) who continued to supply ‘ébauches’ and complete commercial watches throughout his career.”

Ref.: Daniels G., The Art of Breguet, Sotheby’s publications, 1986, P. 5

“The style of the signature, the number, the style of engraving, the shape and finish of the components of the movement can give clues. (sic) A high-grade watch, correct in every detail, but not recorded in the books, must be judged on its merits. Experienced collectors do not need documentary evidence to support their judgement and, as in most fields of art, there is none. A fine watch obviously made in the (or for the) workshops should not be discarded because its existence cannot easily be traced by records.”

Ref.: Daniels G., The Art of Breguet, Sotheby’s publications, 1986, P. 31

“As with dials, so with early cases there is no uniform system of making. (sic) When a number is found it is not always recorded in the books,…“

Ref.: Daniels G., The Art of Breguet, Sotheby’s publications, 1986, P. 33

Return to Paris, 1795

The 20th of April 1795 Breguet returned to Paris, when the political scene in France had stabilised. He returned with many ideas for innovations refining for example the concept of the ‘Montre à Souscription‘. Circa 1807 Breguet brought in his son, Louis – Antoine (born 1776) as a business partner, and from this point the firm became known as ‘Breguet et Fils‘. Breguet had previously sent his son to London to study with the great English chronometer maker, John Arnold, and such was the mutual friendship and respect between the two men that Arnold, in turn, sent his son, John Roger, to spend time with Breguet. Breguet made three series of watches, and the highest numbering of the three reached 5120, so in all it is estimated that the firm produced around 17,000 timepieces during Breguet’s life. With this enormous output it is understandable, that not all pieces were made of even finished ‘in house’. Most of the most simple watches, as well as some of the most complex ones, were bought completely pre-made.

Because of his minute attention to detail and his constant experimentation, no two Breguet pieces are exactly alike. His achievements soon attracted a wealthy and influential clientele: Louis XVI and his Queen Marie – Antoinette, Louis XVIII, George IV (UK), Napoleon Bonaparte, Alexander I (Russia), Prince of Wales, Joséphine de Beauharnais, 1st Duke of Wellington. Following his introduction to the court, Queen Marie – Antoinette developed a fascination for Breguet’s unique self-winding watch and Louis XVI of France bought several pieces. At the very start of his career, Abraham – Louis Breguet mostly used the calibres of the celebrated Jean – Antoine Lépine, which he transformed. Later he developed his own calibers. His watches and clocks are widely regarded as some of the most beautiful and technically accomplished. The business grew from strength to strength, and when Abraham – Louis Breguet died in 1823 it was carried on by his son Louis – Antoine.

Breguet’s production numbering systems

Starting from 1775, at the beginning of his independent work, Breguet mostly used movements (and pre-made watches) provided mostly by the Lépine workshop, or directly by the factory of Gedeon Decombaz, a raw movement manufacturer from Geneva, who also made many of Lépine’s raw movements. These raw movements were just slightly modified, engraved ‘Breguet à Paris’ and remained most likely all un-numbered. Probably as soon as he got master watchmaker in 1784, with an increasing output and more important customers, Breguet introduced a numbering system to keep track of the production details of his watches and their sale date. Some of the very early, unnumbered watches made before 1784 mentioned above, have been stocked in different states of finishing and were completed and sold after 1790 and thus marked with a corresponding production number. Examples of such very early pieces with later production numbers are Nos. 12, 149, 149bis, and 242.

Already Tompion had a numbering system, which was continued by George Graham. In France, Julien LeRoy was the first to use a continuous numbering system. Ferdinand Berthoud and Lépine followed this custom as well. Breguet introduced several numbering systems, which makes the attribution and dating of watches rather difficult, more so, as some numbers either appear more than once or none at all and because the sequence of numbers of different watch types sometimes overlaps (see souscription watches below). The table shows the different numbering systems and approximate dates of their use during production. It is unknown, if Breguet used a different system during his stay in Switzerland (8.1793 – 4.1795). The numbering system for the watches made outside of Breguet’s workshops (Etablissement Mixte de Breguet) is used in parallel with the 3rd series and was active from 1806 (No. 1) to 1832 (No. 2421).

It is important to know, that no Breguet watch is known with a production number which reaches 6000. Hence, a watch signed ‘Breguet’ with a production number higher than 5500 must be considered a forgery. Especially badly Swiss made 19th century, mostly verge forgeries signed ‘Breguet à Paris’ use numbers over 5500.