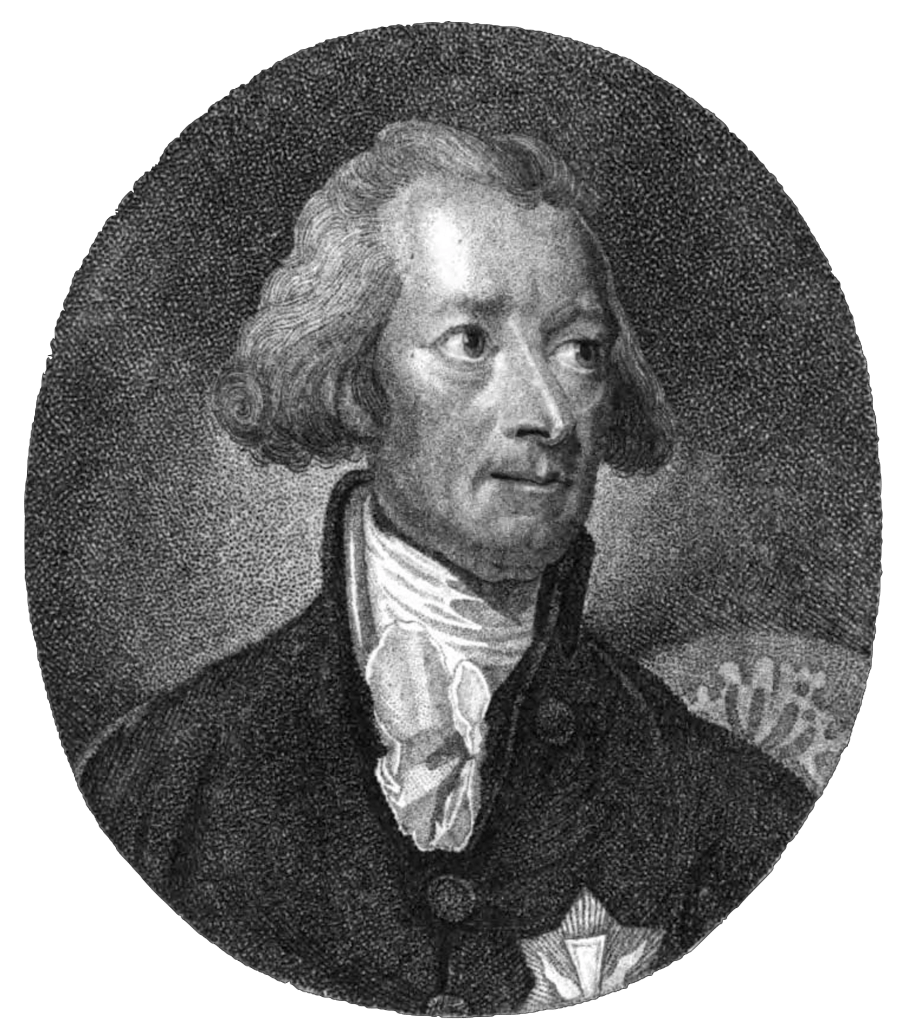

Thomas Mudge (9.1717 – 14.11.1794) was the second son of Zachariah Mudge, headmaster and clergyman, and his wife, Mary Fox. He was born in Exeter. Thomas, when 14 or 15, was sent to London to be apprenticed to George Graham, the eminent clock and watch maker who had trained under Thomas Tompion. Graham’s business was situated in Water Lane, Fleet Street. When Mudge qualified as a watchmaker in 1738 he began to be employed by a number of important London retailers. Whilst making a most complicated equation watch for the eminent John Ellicott, Mudge was discovered to be the actual maker of the watch and was subsequently directly commissioned to supply watches for Ferdinand VI of Spain. He is known to have made at least five watches for Ferdinand, including a watch that repeated the minutes as well as the quarters and hours. (A)

In 1748 Mudge set himself up in business at 151 Fleet Street, and began to advertise for work as soon as his old master, George Graham, died in 1751. Although not Graham’s successor, it was Mudge who brought Grahams principles to perfection. He rapidly acquired a reputation as one of England’s outstanding watchmakers, and is now rightly considered one of the greatest and most influential watch and clock makers of the period. In 1753 he married Abigail Hopkins of Oxford, with whom he had two sons.

Most probably William Dutton, another of Grahams apprentices, worked for Mudge since the opening of latters workshop. Around 1765 he took William Dutton, as partner, singing all subsequent work as Mudge & Dutton. Mudge was to supervise the watch production, while William Dutton took care of the clock business. Around 1755, if not earlier, Mudge invented the detached lever escapement, which he first applied to a clock, but which, in watches, can be considered the greatest single improvement ever applied to them since the invention of the balance spring and which remains a feature in almost every pocket timekeeper made up to and including the present day. (A)

In 1760 Mudge was introduced to Count Hans Moritz von Brühl (20.12.1736 – 9.6.1809), envoy extraordinary from the court of Saxony, who henceforth became a steady patron. In 1765 Mudge was invited as expert by the Board of Longitude to assist at the dismantling of Harrison’s H4. An argument arose with the Board, as Mudge openly spoke about the details of the construction of H4 to the French watchmaker Ferdinand Berthoud, who wanted to take advantage of getting insights into H4’s construction to integrate them into his own work on marine timekeepers. Mudge, as George Graham before him, was a honest, humble and altruist person, who never wanted to patent his developments. He regarded the copying of his principles as an honour. It is in this context that the divulgation of the construction details of H4 to Berthoud need to be understood, he thought to encourage the development of the best possible timekeeper.

Also in 1765 Mudge published the book, ‘Thoughts on the Means of Improving Watches, Particularly those for Use at Sea’. It’s known, that Larcum Kendall worked for the firm for many years. Most of the best finished watches might be made by him.

In 1771, due to ill-health Mudge, quit active business and left London to live in Plymouth with his brother Dr. John Mudge. From that date Mudge worked on the development of a marine chronometer that would satisfy the new rigorous requirements of the Board of Longitude, which had been amended in 1765 after the earlier work of John Harrison (A). He sent the first of these (see below) for trial in 1774, and was awarded 500 guineas for his design.

He completed two others by 1779 (‘Green’: 1777, ‘Blue’: 1776 – 1779) in the continuing attempt to satisfy the increasingly difficult requirements set by the Board of Longitude. They were tested by the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, and declared as being unsatisfactory. There followed a controversy in which it was claimed that Maskelyne had not given them a fair trial. A similar controversy had arisen when John Harrison had been denied the full amount of the 1714 prize by the Board of Longitude. Eventually, in 1792, two years before his death, Mudge was awarded £2,500 by a Committee of the House of Commons who decided for Mudge and against the Board of Longitude, then headed by Sir Joseph Banks.

In 1770 George III purchased a large gold watch produced by Mudge, that incorporated his lever escapement. This he presented to his wife, Queen Charlotte, and it still remains in the Royal collection at Windsor Castle. In 1776 Mudge was appointed watchmaker to the king. In 1789 his wife, Abigail died. Thomas Mudge died at the home of his elder son, Thomas, at Newington Butts, London on 14 November 1794. He was buried at St Dunstan-in -the- West, Fleet Street.

The importance of Thomas Mudge in the development of watches is highly underrated and his importance for the developments in horology was mainly overshadowed by the success and publicity of John Harrison. Even if the principles of John Harrison were ground braking, no other watchmaker at that time reached the quality of manufacture of the Mudge & Dutton firm (A).

Thomas Mudge, Plymouth, No. 1, 1774

As mentioned above, this timekeeper was sent for a trial to Greewich, where it has been largely overlooked and mis-judged. Its balance spring broke twice and there was an accusation that it had been dropped, so it was excluded from the race for the rest of the Longitude Price, even if it has been measured as the most accurate of all candidates (A)! Mudge, had spent all of his economies for research on marine chronometers and most probably his illness, that he could not afford a metal case for this timekeeper, which is now boxed in a beautiful glazed, mahogany case (B).

It has to be emphasised that this marine chronometer made in 1774 by Thomas Mudge remained the most precise timekeeper until 1887! (B)