During the 18th century watchmakers in England and France continued to produce the largest quantity and the best quality watches. In each of these countries their distinctive style was further developed until the end of the century where the exchange between the two countries increased and gave rise to a more uniform style of big, flat watches.

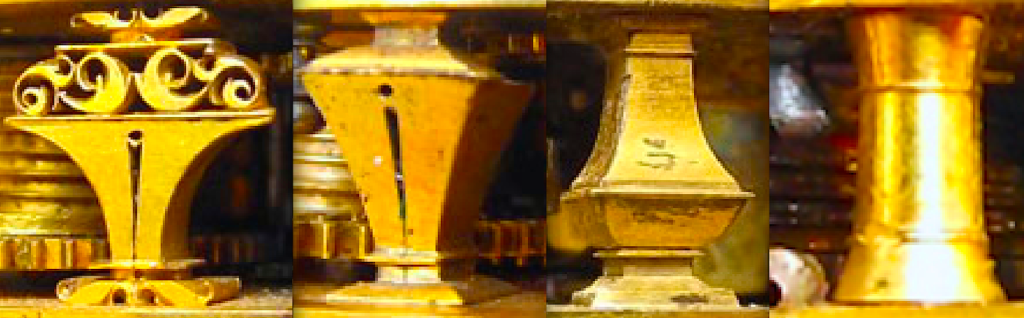

Both countries followed the same change of pillar style, getting away from the tulip and Egyptian type towards the square baluster style, which started to get shorter, thinner and rounder towards the end of the 18th century, especially due to the effort of making smaller and flatter watches. The use of pillars got obsolete, when newer movement configurations took over using separate bridges omitting the back plate, a system invented by French watchmaker Jean – Antoine Lépine and refined by Abraham – Louis Breguet.

In 18th century France called ‘Siècle des Lumières’ (Century of lights) the size of the watches decreased after the death of Louis XIV. During the French regency period (1720 – 1730), the beginning of the reign of Louis XV, the rim of the back plate got usually decorated with a wavy line, sometimes made out of silver. The front winding system of the French got more and more suppressed by the introduction of the hind winding system and the use of dust caps (cuvettes). The dials remained of enamelled copper but lost their cartouches and the bumps, making the dials smooth to the touch and much flatter towards the end of the century.

The cock followed the size shrinkage of the watch movements and got characteristic ‘ears’ between the cock plate and the attachment screws around 1720. In later years the regulator-dial and the cock got almost to equal size, the ‘ears’ disappeared.

Some French watchmakers criticised the cylinder escapement refined by George Graham, calling it not reliable enough. Indeed, the verge escapement being more robust than the delicate cylinder escapement. Nevertheless, despite criticisms, most French watchmakers later introduced the cylinder escapement. Julien Le Roy and his son Pierre experimented a lot with slight modifications to the cylinder escapement. Later watchmakers such as Jean – Antoine Lépine and Abraham – Louis Breguet introduced the virgule escapement and perfectioned the lever escapement, invented around 1755 by the English watchmaker Thomas Mudge. Around 1760 some French watchmakers such as Ferdinand Berthoud followed the steps of Pierre Le Roy (son of Julien) and their English concurrence in developing high precision watches to compete for the Longitude Prize.

The cases were plain with minimal engraved decoration. Latter changed around 1740, when Julien Le Roy started to make very luxurious watches, which cases were inlaid with precious stones, and mostly made of three colored gold. Later the cases got elaborate enameled scenes, with a preference for romantic topics.

These romantic scenes were in fashion after 1720, when the painter Jean – Antoine Watteau (10.10.1684 – 18.7.1721) introduced the genre of the ‘fêtes galantes’ which were inspired by Italian comedy and ballet. Later these scenes were enamelled on the back of gold cases. The best enamel work coming from Geneva. Around 1760, when the fashion of smaller watches got introduced (wrongly referred to as ‘women’s watches’) also very elaborate, female portraits were enamelled on the backs of gold cases. Towards 1770 quilloched geometrical patterns appeared on the cases which were overlaid with colored, tanslucent enamel. The Russian jeweller Karl Fabergé perfected this decorative form and made it his signature feature on jewelry towards the end of the 19th century.

Jean – Antoine Lépine followed this fashion until his optimisations of style and mechanics made the watches even smaller (up to 25mm in diameter) and he also started to use exclusively Arabic numerals on dials already starting from the 1760s. Lépine and later Abraham – Louis Breguet, introduced enormous watches (up to 65mm in diameter) taking up the development of pocket chronometers in England, but which were extremely flat, launching a new fashion. This reduction in thickness was achieved thanks to the refinement of the cylinder escapement, the development of other escapement types and the introduction of the Lépine caliper. Actually many ébauches (raw, unfinished movements), even those for emminent watchmakers such as Lépine or Breguet were made in Switzerland and then sent to France for finishing.

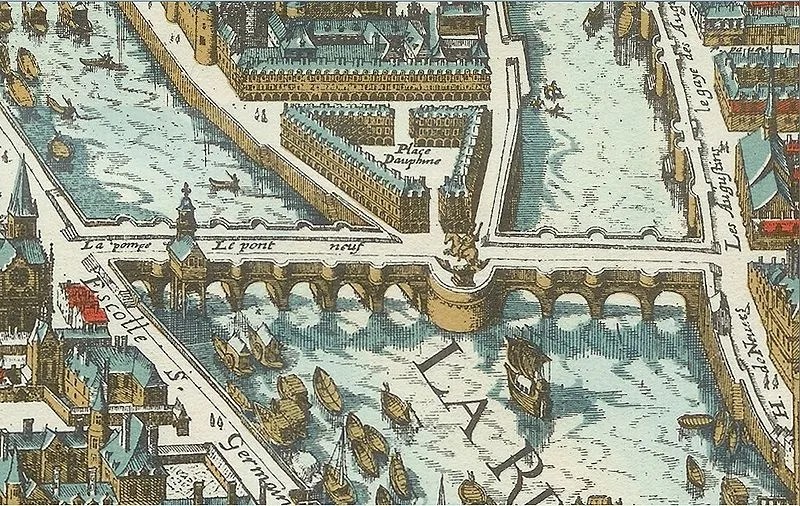

All important French watchmakers such as Berthoud, Lépine and Breguet were situated at the ‘Quai de l’Horloge’, as they could find the gold – and silversmiths manufacturing the watch cases around the corner at the ‘Quai des Orfèvres’ and the enamelers for the dials in between these two locations on the ‘Place Dauphine’ (renamed ‘Place Thionville’ for a short period of time). The name of this place can be found written on the counterenamel of some watch dials from Lépine, Breguet and others at the end of the 18th century. This site was used by watchmakers since the reign of Louis XIV.

An important feature which will change between the reigns of Louis XV and his grand son Louis XVI, is the style of the cock decoration. Remaining of same size the cocks manufactured during the reign of Louis XV show an asymmetrical rocaille decoration whereas starting from about 1777 the decoration got symmetrical and showed attributes of greek mythology such as ‘lyres’.