Breguet was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland to Jonas – Louis Breguet and Suzanne – Marguerite Bollein. The young Breguet soon astonished his master with his aptitude and intelligence, and to further his education he took evening classes in mathematics at the Collège Mazarin (Paris) under Abbé Marie, who became a friend and mentor to the young watchmaker. Breguet was allowed to marry in 1775 after finishing his apprenticeship. He and his bride, Cécile Marie – Louise L’Huillier, set up their home and the Breguet watchmaking company; its first known address was at ’51 Quai de l’Horloge’ in ‘Île de la Cité’ in Paris. Unfortunately the house number is no longer there, as at some point the street numbers have been completely changed.

As Breguet’s fame gradually increased he became friendly with revolutionary leader Jean – Paul Marat, who also hailed from Neuchâtel. Breguet invented or perfected innovative escapements, including the final development of the tourbillon, the overcoil (an improvement of the balance spring with a raised outer coil, invented by John Arnold) and perfected automatic winding mechanisms. Within ten years Breguet had commissions from the aristocratic families of France and even the French queen, Marie – Antoinette. Cécile died in 1780.

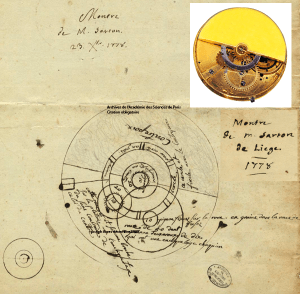

Breguet met Abraham – Louis Perrelet (supposedly the inventor of the automatic, self winding mechanism (now contested and invention of the self-winding system is attributed to the Belgian Hubert Sarton who deposited a drawing to the ‘Académie Royale des Sciences’ in Paris, the 16.12.1778), later improved by Breguet and named ‘perpetuelle’) in Switzerland and he became a Master Clockmaker in 1784. In 1787 Breguet established a partnership with Xavier Gide and latter’s brother, which lasted only until 1791. Ca. 1792 the Duke of Orléans went to England and met John Arnold, then Europe’s leading watch and clockmaker. The Duke showed Arnold a clock made by Breguet, who was so impressed that he immediately travelled to Paris and asked Breguet to accept his son as an apprentice.

In 1793 Jean – Paul Marat discovered that Breguet was marked for the guillotine, possibly because of his friendship with Abbé Marie (and/or his association with the royal court); in return for his own earlier rescue by Breguet, Marat arranged for a safe-pass that enabled Breguet to escape to Switzerland the 12th of August 1793, from where he travelled to England. This same year the 13th of July 1793, Marat was stabbed in his bath tub by Charlotte Corday from Caen. Before he died he cried to his wife “Aidez-moi, ma chère amie!” (“Help me, my dear friend!”). Breguet’s journey to Switzerland included a short visit in Ferney and Geneva and a longer stay in the region of Neuchâtel and Le Locle. Afterwards he remained in London for some time, during which he worked for King George III.

The 20th of April 1795 Breguet returned to Paris, when the political scene in France had stabilised. He returned with many ideas for innovations refining for example the concept of the ‘Montre à Souscription‘. Circa 1807 Breguet brought in his son, Louis – Antoine (born 1776) as a business partner, and from this point the firm became known as ‘Breguet et Fils‘. Breguet had previously sent his son to London to study with the great English chronometer maker, John Arnold, and such was the mutual friendship and respect between the two men that Arnold, in turn, sent his son, John Roger, to spend time with Breguet. Breguet made three series of watches, and the highest numbering of the three reached 5120, so in all it is estimated that the firm produced around 17,000 timepieces during Breguet’s life. With this enormous output it is understandable, that not all pieces were made of even finished ‘in house’. Most of the most simple watches, as well as some of the most complex ones, were bought completely pre-made.

Because of his minute attention to detail and his constant experimentation, no two Breguet pieces are exactly alike. His achievements soon attracted a wealthy and influential clientele: Louis XVI and his Queen Marie – Antoinette, Louis XVIII, George IV (UK), Napoleon Bonaparte, Alexander I (Russia), Prince of Wales, Joséphine de Beauharnais, 1st Duke of Wellington. Following his introduction to the court, Queen Marie – Antoinette developed a fascination for Breguet’s unique self-winding watch and Louis XVI of France bought several pieces. At the very start of his career, Abraham – Louis Breguet mostly used the calibres of the celebrated Jean – Antoine Lépine, which he transformed. Later he developed his own calibers. His watches and clocks are widely regarded as some of the most beautiful and technically accomplished. The business grew from strength to strength, and when Abraham – Louis Breguet died in 1823 it was carried on by his son Louis – Antoine.

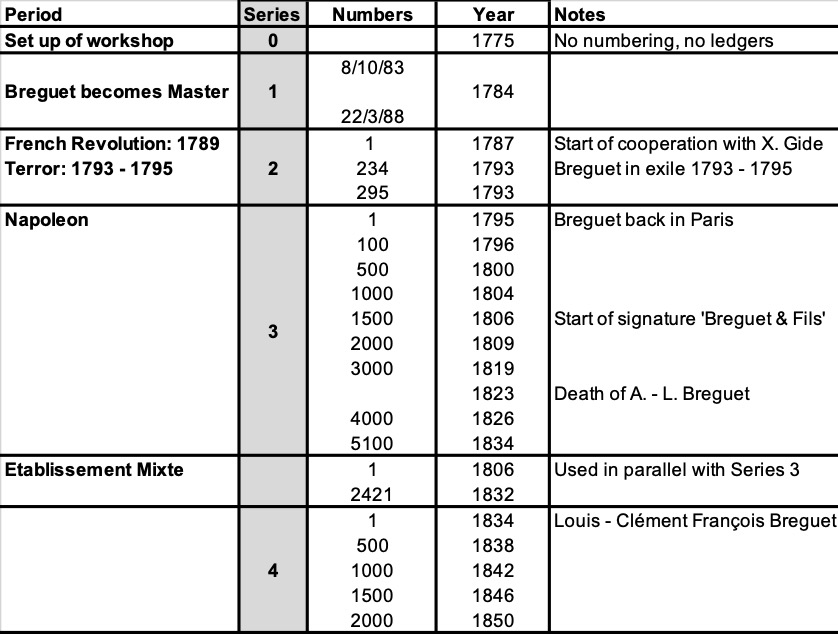

Breguet’s production numbering systems

Starting from 1775, at the beginning of his independent work, Breguet mostly used movements (and pre-made watches) provided mostly by the Lépine workshop, or directly by the factory of Gedeon Decombaz, a raw movement manufacturer from Geneva, who also made many of Lépine’s raw movements. These raw movements were just slightly modified, engraved ‘Breguet à Paris’ and remained most likely all un-numbered. Probably as soon as he got master watchmaker in 1784, with an increasing output and more important customers, Breguet introduced a numbering system to keep track of the production details of his watches and their sale date. Some of the very early, unnumbered watches made before 1784 mentioned above, have been stocked in different states of finishing and were completed and sold after 1790 and thus marked with a corresponding production number. Examples of such very early pieces with later production numbers are Nos. 12, 149, 149bis, 242.

Already Tompion had a numbering system, which was continued by George Graham. In France, Julien LeRoy was the first to use a continuous numbering system. Ferdinand Berthoud and Lépine followed this custom as well. Breguet introduced several numbering systems, which makes the attribution and dating of watches rather difficult, more so, as some numbers either appear more than once or none at all and because the sequence of numbers of different watch types sometimes overlaps (see souscription watches below). The table shows the different numbering systems and approximate dates of their use during production. It is unknown, if Breguet used a different system during his stay in Switzerland (8.1793 – 4.1795). The numbering system for the watches made outside of Breguet’s workshops (Etablissement Mixte de Breguet) is used in parallel with the 3rd series and was active from 1806 (No. 1) to 1832 (No. 2421).

It is important to know, that no Breguet watch is known with a production number which reaches 6000. Hence, a watch signed ‘Breguet’ with a production number higher than 5500 must be considered a forgery. Especially badly Swiss made 19th century, mostly verge forgeries signed ‘Breguet à Paris’ use numbers over 5500.

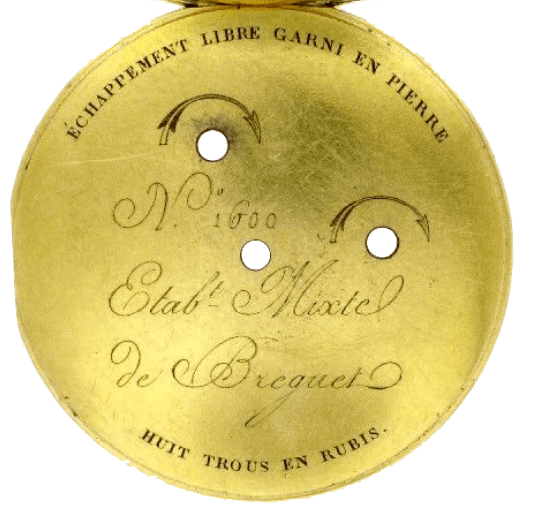

Etablissement Mixte

At the beginning of Breguet’s career, Breguet does not differentiate between pre-fabricated watches and own developments, at least not on the watches itself (with rare exceptions marked ‘Repasée par Breguet’). The dials of watches of this type are not signed, following the reasoning above. However, in the ledgers it can be seen, which pieces received more or less attention from the workshop.

The same procedure will be applied during Breguet’s exile (1793/94). During the ‘terror years’, when A. – L. Breguet was absent from his workshop in Paris, latter sold a big amount of such pre-fabricated pieces, which sometimes were not even finished in Paris, but completely build in external workshops. Such pieces are sometimes not even numbered, so they must be identified applying George Daniel’s suggestion of ‘judging them on their quality’.

Starting from 1806, as a marketing genius, Breguet will introduce the term of ‘Etablissement Mixte’, which means ‘mixed workshop’ and which indicates that the watch is not completely made in house, without outing which procedures were made in external facilities and which in his own workshop.

In rare instances watches are double signed, one signature for the workshop producing the pre-fabricated piece, the second declares the ‘repassage’ by another workshop, which then finally sells the watch.

Sometimes French clockmakers (who not always had the expertise to build watches) would also buy completely pre-fabricated watches, which are signed with their name, but build in external workshops. These watches would complement their offer and allow for additional income.

Louis – Clement – François Breguet (22.12.1804 – 27.10.1883)

He took over the business together with a family associate after the retirement of his father Louis – Antoine Breguet in 1833. The firm was renamed ‘Breguet Neveu & Cie’. By 1833 they re-introduced a small series of ‘sympathique’ pieces (see below), which were intended to be of as simple construction as possible.

Between 1835 and 1840 he standardized the company product line of watches, then making 350 watches per year, and diversified into scientific instruments, electrical devices, recording instruments, an electric thermometer, telegraph instruments and electrically synchronized clocks. In 1870 he transferred the leadership of the company to Edward Brown. Breguet then focused entirely on the telegraph and the nascent field of telecommunications. Louis – Clement was the grandfather of Louis Charles Breguet, aviation pioneer (co-founder of Air France) and aircraft manufacturer.