Ferdinand Berthoud (18.03.1727 – 20.06.1807) was born in Plancemont, canton of Neuchâtel, Switzerland to Judith and Jean Berthoud, a carpenter and architect. He showed an early interest in horology and in march 1741 he started a four year apprenticeship to his older brother Jean – Jacques. With an exemplary recommendation by his brother he traveled to Paris in 1745 to perfection his skills. He took advantage from the network his brother had in Paris and starting from 1753 he already had a remarkable reputation. He built a long case clock with equation of time which granted him the support of the Royal Academy of Sciences, in the name of King Louis XV. The 4th of November 1753 he became maître (master), a rare honour for a non French citizen. He subsequently opened a workshop at the Rue du Harlay (the same street as the workshop of Julien Le Roy). The 20th of November 1754 he submitted a project to the Royal Academy of Sciences showing a ‘marine timekeeper’, the first recorded mentioning of efforts towards resolving the Longitude Problem by Berthoud, but the machine itself has never been recorded. Along with Julien Le Roy, his son Pierre, and Jean Romilly, Berthoud was asked to contribute to the encyclopaedia of Diderot and d’Alembert in 1755. His first book on horology was published on 1759 (see section about historical books and ephemera). At some point Berthoud wanted to patent his new invention of temperature compensation for the balance spring, only to find out that the system had already been invented by John Jefferys, who together with John Harrison was about to develop the most accurate watch to date.

In early 1761 he presented his ‘Horloge de Marine No. 1’ which finally didn’t work very well. In a letter written by Berthoud to Pierre Jaques-Droz in 1763 Berthoud expresses his admiration for Henry Sully and Julien Le Roy, which shows in the use and further development of their principles. The same year he was nominated by the King to examine Harrison’s H4. His trip to London in May 1763 was in vain, as Harrison refused to show H4 to Berthoud. But upon his return to Paris Berthoud was elected foreign member to the British Royal Academy of Sciences from the 16th of February 1764 on, which increased his international reputation in the field of precision horology. Daniel Bernoulli a very well respected Swiss mathematician and physicist and already member of the reputed society, was in favour of Berthoud’s election. At the beginning of 1766 he returned to London to finally get to see H4. Harrison expected a prime of 4000£ for the disclosure of the secrets of H4, but Berthoud arrived with only 500£. Not discouraged by Harrison’s repeated refusals, Berthoud dined with Thomas Mudge. Mudge, member of the disclosure panel of the board of Longitude, told Berthoud all he knew about H4, thinking to act in the interest of the board that the knowledge should be disseminated. He might have acted in the interest of the board, but against the interests of Harrison! Berthoud seemed satisfied with his trip, but still had no insights into H4. Fortunately for Harrison, Berthoud was not able to make good use of what Mudge had told him. But Ferdinand Berthoud had seen the tools used by British specialists to built Marine timekeepers which he tried to get for himself through sponsoring by the King.

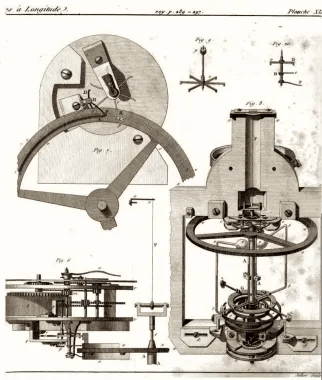

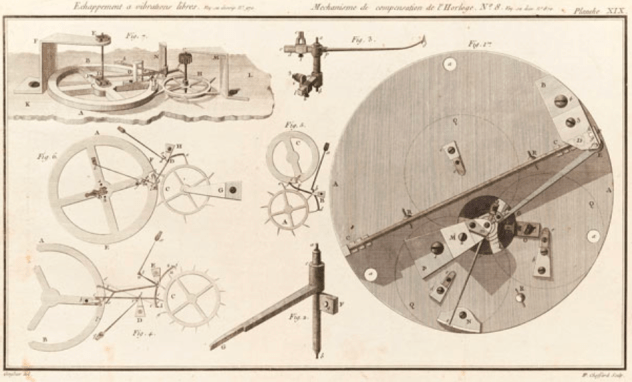

Berthoud’s most important rival was Pierre Le Roy (fils) who used a different approach to obtain a working marine chronometer. Two of Berthoud’s marine timekeepers, Nr. 6 and Nr. 8 and one made by Pierre Le Roy were submitted to testing in two phases from December 1768 until 1772. Berthoud’s Nr. 8 performed perfectly, even if Le Roy’s system would have been more reliable, but unfortunate circumstances gave Berthoud advantages which lead him to receive the affiliation ‘Horloger Méchanicien du Roi et de la Marine’, the 1st of April 1770 for his work. Le Roy couldn’t match Berthoud’s extrovert energy, lobbying and marketing, even though he criticised Berthoud publicly. Le Roy withdraw from the competition completely. Berthoud produced 75 marine chronometers in 35 years. Pierre Le Roy’s ground breaking work on marine chronometers was long forgotten, until the interest and research in the history of watchmaking during the late 19th century redeemed his reputation.

Towards the end of the 18th century Berthoud’s efforts were overtaken by John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw in London and by his brilliant nephew (Pierre) Louis Berthoud (1754 – 1813), who became his apprentice in 1769, at the age of 15. In 1770 Ferdinand decided not to work on simple watches for private clients any longer, concentrating solely on marine chronometers. All the questions in current research regarding watchmaking precision were studied by Berthoud: escapements, whether of the cylinder, detent or lever type; the problem of friction; the isochronism of the sprung balance; thermal compensation; the indication of true and mean time. His research was often conducted for the benefit of both marine clocks and their civil counterparts. His manufacture built somehow cheaper and simple watches to finance his research on marine chronometers. In 1775 he passed the supervision of his workshop to his nephew Henry Berthoud (Louis’ brother). The leadership of Henry proved disastrous and at his death by suicide the 29th of June 1783 he left a dept of 60’000 livres.

Ferdinand’s nephew Louis Berthoud was leading the workshop after the death of Henry from 1784 on. The size of the workshop was reduced and the work outsourced to other workshops, Ferdinand but mostly Louis Berthoud only being responsible for the finishing of the movements. However, Louis was allowed to sign his work only from about 1787 on. He retained a life long resentment against Ferdinand for not giving him enough credit for his important contributions. Louis was named ‘Horloger de la marine Impériale’ in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte preferring him to Abraham – Louis Breguet of whom he was disappointed as the perpetual repeating watch (No. 216) bought from him for his ‘Egypt campaign’ in 1798 didn’t resist the sand and broke down. Moreover, rumours state that a Breguet jumping hour model made Napoleon miss an important meeting. It is transmitted that Napoleon then smashed the watch to pieces.

Ferdinand Berthoud signed his more important pieces, on which he mostly worked himself, with his full name, the less important pieces made or later finished in his workshop (after 1770), which he didn’t work on, were signed ‘Fd. Berthoud’. Watches signed only ‘Berthoud à Paris’ are mostly contemporary (Swiss made) fakes, more so, if they are not numbered. However, some original clocks survive which are signed ‘Berthoud à Paris’. Ferdinand Berthoud remained a quite modest and assuming watchmaker until the end of his life. Napoleon Bonaparte made Ferdinand Berthoud Knight of the ‘Légion d’honneur’ in 1802. He died in his small house in Grossly near Montmorency (north of Paris) at the age of 80 in 1807.

The workshop of Ferdinand Berthoud was sponsored by the King Louis XVI in 1782. Berthoud was allowed to follow his research on marine timekeepers and to use the facilities and what he produced, but the workshop and its content remained property of the King. Upon the masters death in 1807, the whole content of his workshop was transferred to the ‘Musée du Conservatoire des arts et métiers’ in Paris, founded 1794, where it still can be admired. Most of Berthoud’s marine chronometers, as well as his tools and his workbench, are permanently exposed at the museum.