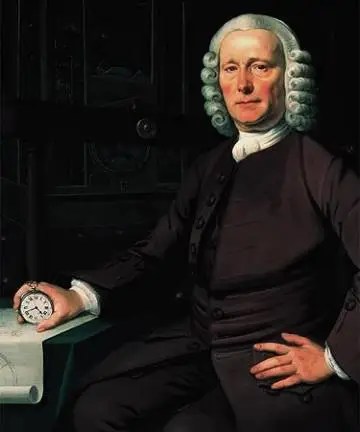

John Harrison (03. 04. 1693 – 24. 03. 1776) was born in Foulby, in West Yorkshire. His father worked as a carpenter at the nearby Nostell Priory estate. Around 1700, the Harrison family moved to the Lincolnshire village of Barrow upon Humber. Following his father’s trade as a carpenter, Harrison built and repaired clocks in his spare time. Legend has it that at the age of six, while in bed with smallpox, he was given a watch to amuse himself and he spent hours listening to it and studying its moving parts.

Harrison built his first longcase clock in 1713, at the age of 20. The mechanism was made entirely of wood, which was a natural choice of material.

Three of Harrison’s early wooden clocks have survived: the first (1713) is at the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers’ collection in the Guildhall; the second (1715) is in the Science Museum; and the third (1717) is at Nostell Priory in Yorkshire, the face bearing the inscription ‘John Harrison, Barrow’.

In the early 1720s, Harrison was commissioned to make a new turret clock at Brocklesby Park, North Lincolnshire. The clock still works and like his previous clocks has a wooden movement of oak and lignum vitae. Between 1725 and 1728, John and his brother James, also a skilled joiner, made at least three precision longcase clocks, again with the movements and longcase made of oak and lignum vitae. The grid-iron pendulum (alternating brass and iron rods assembled so that the different expansions and contractions cancel each other out) was developed by him during this period. These precision clocks are thought by some to have been the most accurate clocks in the world at the time, even better than his famed H4!

Harrison was a man of many skills and he used these to systematically improve the performance of the pendulum clock. Another example of his inventive genius was the grasshopper escapement – a control device for the step-by-step release of a clock’s driving power. Developed from the anchor escapement, it was almost frictionless, requiring no lubrication because the pallets were made from lignum vitae. This was an important advantage at a time when lubricants (vegetal / animal oils) and their degradation were little understood.

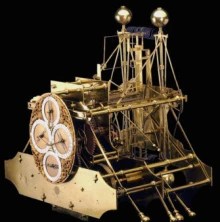

In 1730, Harrison designed a marine clock to compete for the Longitude Prize and travelled to London, seeking financial assistance. He presented his ideas to Edmond Halley (discoverer of the Halley`s comets periodicity in 1705), the Astronomer Royal, who in turn referred him to George Graham. Graham must have been impressed by Harrison’s ideas, for he loaned him money to build a model of his ‘Sea clock’. As the clock was an attempt to make a seagoing version of his wooden pendulum clocks, which performed exceptionally well, he used wooden wheels, roller pinions and a version of the ‘grasshopper’ escapement. Instead of a pendulum, he used two dumbbell balances, linked together.

It took Harrison five years to build his first Sea Clock (H1). He demonstrated it to members of the Royal Society who spoke on his behalf to the Board of Longitude. The clock was the first proposal that the Board considered to be worthy of a sea trial. In 1736, Harrison sailed to Lisbon on HMS Centurion and returned on HMS Orford. On their return, both the captain and the sailing master of the Orford praised the design. The master noted that his own calculations had placed the ship sixty miles east of its true landfall which had been correctly predicted by Harrison using H1.

This was not the transatlantic voyage demanded by the Board of Longitude, but the Board was impressed enough to grant Harrison £500 for further development. Harrison moved on to develop H2, a more compact and rugged version. In 1741, after three years of building and two of on-land testing, H2 was ready, but by then Britain was at war with Spain in the War of Austrian Succession and the mechanism was deemed too important to risk falling into Spanish hands. In any event, Harrison suddenly abandoned all work on this second machine when he discovered a serious design flaw in the concept of the bar balances.

He had not recognised that the period of oscillation of the bar balances could be affected by the pitching action of the ship. It was this that led him to adopt circular balances in the Third Sea Clock (H3). The Board granted him another £500, and while waiting for the war to end, he proceeded to work on H3.

Harrison spent seventeen years working on this third ‘sea clock’ but despite every effort it seems not to have performed exactly as he would have wished. Certainly in this machine Harrison left the world two enduring legacies – the bimetallic strip and the caged roller bearing. The failure of the sea clocks 1, 2 and 3 were due mainly to the fact that their balances though large, did not vibrate quickly enough to confer the property of stability on the timekeeping. Around 1750 Harrison had also come to this conclusion and abandoned the idea of the ‘Sea clock’ as a timekeeper, realising that a watch sized timekeeper would be more successful as it could incorporate a balance which though smaller, oscillated at a much higher speed. A watch would also be more practicable, another factor required by the Longitude Act of 1714.

After pursuing various methods during thirty years of experimentation, Harrison moved to London where to his surprise he found that some of the watches made by Graham’s successor Thomas Mudge kept time just as accurately as his huge sea clocks. It is possible that Mudge was able to do this after the early 1740s thanks to the availability of the new ‘Huntsman’ or ‘Crucible’ steel produced by Benjamin Huntsman sometime in the early 1740s which enabled harder pinions but more importantly, a tougher and more highly polished cylinder escapement to be produced. Harrison then realised that a mere watch after all could be made accurate enough for the task and was a far more practical proposition for use as a marine timekeeper. He proceeded to redesign the concept of the watch as a timekeeping device, basing his design on sound scientific principles.

All watches signed by John Harrison are in public collections. Just two watches made by his son William survive: one is in a public collection and one in a private British collection.

During his lifelong search to win the Longitude prize Harrison got several grants adding up to 23’000£ to pursue his research for the perfect timekeeper, but actually he never officially won the Longitude Prize!

The ‘Jefferys’ watch

Harrison had already designed a precision centre seconds watch for his own personal use, which was made for him by the London watchmaker John Jefferys c. 1752 – 53. This watch incorporated a novel frictional rest escapement and was not only the first to have a compensation for temperature variations but also contained the first ‘going fusee’ of Harrison’s design which enabled the watch to continue running whilst being wound. These features led to the very successful performance of the ‘Jefferys’ watch so therefore Harrison incorporated them into the design of two new timekeepers which he proposed to build (H4 and the ‘lesser watch’). These were in the form of a large watch and another of a smaller size but of similar pattern. Constructed by John Jefferys and his apprentice Larcum Kendall, the watch turns out to be Harrison’s breakthrough timepiece. He had already devoted decades –and spent thousands of pounds advanced by Parliament trying to make an accurate shipboard clock. But clocks are bulky and poorly suited to shipboard swaying, which can disrupt their internal mechanisms. And using techniques obscured by a fire damage (see below), Jefferys drastically downsized mechanisms for temperature compensation and friction reduction. For the first time, every gear in a pocket watch was set on a jewelled bearing.

At the end of the 19th century, a dealer offered Harrison’s personal pocket watch to the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers.

“They really wanted this watch, but as far as they were concerned it was purely sentimental,”

Sir George White, keeper of the Clockmakers‘ Museum collections, recounts. The price was too high, so they let it go. The watch passed into the stock of one Mr. Rust, a jeweller whose London shop was subsequently bombed by the Luftwaffe during WWII. His vault fell several stories to the basement and cooked overnight in a fire. The watch survived, though the white enamel face turned black and the metal gearing softened so that it no longer ticked. In this sorry state, Harrison’s watch passed into the Clockmakers’ safekeeping.

“It’s a miracle Mr. Rust didn’t bin it. He’d no way of knowing that the watch would come to have monumental importance. I don’t think anyone expected it to be as good as it was,”

White says. In this watch, all the problems of marine chronometry were essentially resolved. Harrison’s next prototype chronometer, much smaller than the one he had contemplated before his encounter with Jefferys, was to become H4. The ‘Jefferys’ watch is the first using a temperature compensation an can thus be regarded as the first precision watch.

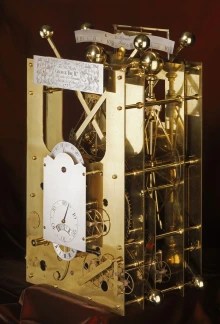

John Harrison, London, ‘H4’, No. 1, 1759

Aided by some of London’s finest workmen (most probably Larcum Kendall replacing Jefferys who died 1754), Harrison proceeded to design and make the world’s first successful marine timekeeper that allowed a navigator to accurately assess his ship’s position in longitude. The huge watch (13.3cm diameter, 1.5kg) has a novel type of ‘vertical’ escapement, which is often incorrectly associated with the ‘verge’ escapement, which it superficially resembles. However, the action of the frictional rest escapement enables the balance to have a large arc. In comparison, the verge’s escapement has a recoil with a limited balance arc and is sensitive to variations in driving torque. The D shaped pallets of Harrison’s escapement are both made of diamond, a considerable feat of manufacture at the time. For technical reasons the balance was made much larger than in a conventional watch of the period, and the vibrations controlled by a flat spiral steel spring. The movement also has centre seconds motion with a sweep seconds hand. The third wheel is equipped with internal teeth and has an elaborate bridge similar to the pierced and engraved bridge for the period. It runs at 5 beats (ticks) per second, and is equipped with a tiny remontoire. A balance-brake stops the watch half an hour before it is completely run down, in order that the remontoire does not run down also. Temperature compensation is in the form of a ‘compensation curb’ (or ‘Thermometer Kirb’ as Harrison called it). This takes the form of a bimetallic strip mounted on the regulating slide, and carrying the curb pins at the free end. During its initial testing, Harrison dispensed with this regulation using the slide, but left its indicating dial or figure piece in place. The watch is equipped with a system called ‘Harrison’s maintaining power’, which consists of a brass (in later watches in steel) lever acting on a ratchet at the base of the fusee, permitting to wind the watch while it still runs.

Harrison showed everyone that it could be done by using a watch to calculate longitude. This was to be Harrison’s masterpiece, resembling an oversized pocket watch from the period. It is engraved with Harrison’s signature, marked Number ‘1’ and dated ‘AD 1759’.

John & William Harrison, London, ‘H5’, No. 2, 1770

Harrison began working on his second ‘Sea watch’ (H5) while Kendall made good progress on his copy of H4. The Board of Longitude was asked to consider H5 and K1 as the two copies of H4, but told John and William, in no uncertain terms, that both copies of H4 should be made by the Harrison’s. After three years he had had enough; Harrison felt “extremely ill used by the gentlemen who I might have expected better treatment from” and decided to enlist the aid of King George III. He obtained an audience with the King, who was extremely annoyed with the Board. King George tested the watch No. 2 himself in his own observatory and after ten weeks of daily observations between May and July in 1772, found it to be accurate to within one third of one second per day. King George then advised Harrison to petition Parliament for the full prize after threatening to appear in person to dress them down. Finally in 1773, when he was 80 years old, Harrison received a monetary award in the amount of £8,750 from Parliament for his achievements, but he never received the official award (which was never awarded to anyone). He was to survive for just three more years.