The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in the period from about 1760 to sometime between 1820 and 1840. This transition included going from hand production methods to machines, new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, improved efficiency of water power, the increasing use of steam power, the development of machine tools and the rise of the factory system. Textiles were the dominant industry of the Industrial Revolution in terms of employment, value of output and capital invested; the textile industry was also the first to use modern production methods.

The Industrial Revolution marks a major turning point in history; almost every aspect of daily life was influenced in some way. In particular, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. Some economists say that the major impact of the Industrial Revolution was that the standard of living for the general population began to increase consistently for the first time in history, although others have said that it did not begin to meaningfully improve until the late 19th and 20th centuries. At approximately the same time the Industrial Revolution was occurring, Britain was undergoing an agricultural revolution, which also helped to improve living standards.

The Industrial Revolution began in the United Kingdom and most of the important technological innovations were British. Mechanized textile production spread to continental Europe in the early 19th century, with important centers in France. A major iron making center developed in Belgium. Since then industrialisation has spread throughout the world. The precise start and end of the Industrial Revolution is still debated among historians, as is the pace of economic and social changes. GDP per capita was broadly stable before the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy, while the Industrial Revolution began an era of per-capita economic growth in capitalist economies. Economic historians are in agreement that the onset of the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in the history of humanity since the domestication of animals and plants.

The First Industrial Revolution evolved into the Second Industrial Revolution in the transition years between 1840 and 1870, when technological and economic progress continued with the increasing adoption of steam transport (steam-powered railways, boats and ships), the large-scale manufacture of machine tools and the increasing use of machinery in steam-powered factories.

Pierre – Frédéric Ingold (6.7.1787 – 10.10.1878)

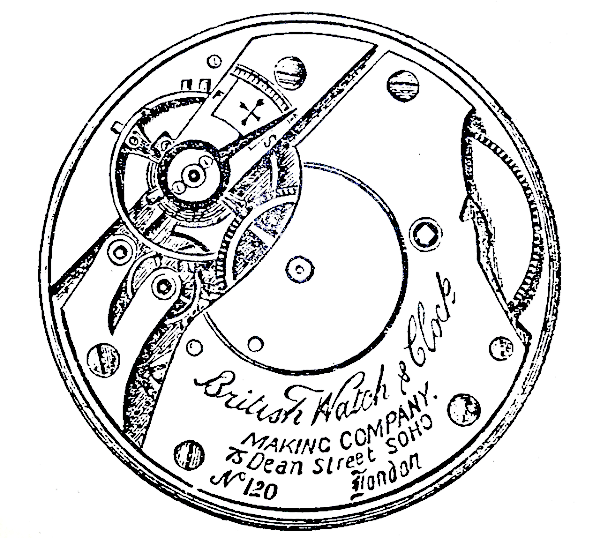

The first real attempt to change watch manufacture was the arrival of Pierre-Frédéric Ingold from Switzerland in circa 1840. Trained by Breguet from 1817 to 1823, he had the idea of using machinery, basically an adapted lathe requiring some skill by its operator, to manufacture movement plates. He had already failed to convince both the Swiss and the French of his system and so it was to prove the same in London. He set up a workshop at 75 Dean Street, complete with equipment, and set about forming the ‘British Watch and Clockmaking Company ‘for which there were three prospectuses in 1842 and three patents, including one in December 1843 for the plate machine and a wheel press with an important four-pillar guide system for the punch and die. The company was to be established by an Act of Parliament, but failed on the second reading of the Bill on the 31st of March 1843. Ingold argued that the usual division of labour was wasteful and that the application of his machinery would revitalise the industry, whereas the opposition, mainly those traditionalists, argued that Ingold was somewhat of a speculator and nothing concrete had as yet been established and that the machines set-up by him didn’t have the capacity to produce as he asserted and needed far more skilled use than this method should require.

There are, though, a very few watch movements and watches known to have been made using his methods so the machinery must’ve been up and running in Dean Street and it is known that one found its way, in 1863, to the workshops of Gillet & Bland in Croydon. Ingold left England and moved to America where machine manufacturing was about to take off with the methods used by, amongst other, Aaron Dennison. But the seed had been sown and it was to Dennison himself having moved to England, Ehrhardt and others to take forward the machine-making of watches, over-coming a number of fears, for instance the fusee was replaced by a dummy fusee which allowed the continuation of anti-clockwise winding, but may well have been too late as the country was now seeing large imports of the mass-produced watches of America and Switzerland.

Taken and modfied from: horologist.co.uk