The forerunner of Breguet’s ‘souscription’ watch has been invented as early as 1777, by the Swiss watchmaker Jacques – Frédéric Houriet. He has described its development and construction in one of his manuscripts, where all the basics of the later refined version by Breguet are already mentioned. The single hand watch constructed using as few pieces as possible was quite bulky and as Houriet just sold around 100 in Zurzach (Switzerland) on a market, he didn’t continue to pursue its development. He must have shared the idea with Abraham – Louis Breguet, who regularly visited Houriet in Le Locle and who took up Houriet’s idea and started the development and first refinements around 1791. The first experimental versions (see below) show still much similarity with Houriet’s design. During Breguet’s exile in Switzerland approximately in 1794, he continued the development of the ‘souscription’ watch most likely with contribution of his friend and host Houriet.

He then continued their construction only after his return to Paris in 1795. These watches were also developed to contain as few components as possible, so to be affordable by less wealthy clients. The concept was to have the watch paid in four instalments, 25% paid upon order and the rest at receipt of the watch. Finally the watches cost between 550 and 900 Francs, which corresponded to a one years salary of a worker at that time, so not really affordable at all!

The dial: Normally made of enamelled copper, with Arabic numerals and five minute separations. The dial is so big, that the time can be read with the resolution of one minute. The dials of some smaller versions are of guilloched silver or gold. Some enamelled dials got replaced during the 19th century with such guilloched ones. These metal dials have always Roman numerals. Earlier dial versions are fixed by screws or pins from the rim, later versions with a single screw through the dial near ’12’ -or ‘6’. The signature placement and style varies. Earlier versions are signed below ’12’ or above ‘6’ in cursive style or Roman capital letters. Later the signature is placed on the edge of the dial. A secret signature below ’12’ is introduced in 1796 to fight counterfeits, almost all enamelled dials have it. This minute signature is made with a pantograph and consists of: ‘Souscription, No.—, Breguet’.

The hand: The main feature of this watch is the single hand. There is no minute work. The hand is made of blued steel, is of ‘Breguet’ type and has a very long tip. The tip mostly has a small ‘bump’ of varying shape towards the end, earlier versions lack this feature, as do late replacements. Some very rare exceptions which are straight and not of ‘Breguet’ type exist, these are mounted exclusively on later, smaller souscription watches.

The case: The earliest experimental versions have a silver or gold case, with no cuvette, which has a typical late 18th century ‘piston’ stem and ovoid bow. Intermediate examples retain the same shape, but have a gold front -and rear rim associated with a silver case and no cuvette. Their stem is a short ball pierced by a circular bow. Late versions have mostly a gold case, no cuvette and the ball shaped stem with circular bow gets standard. The backs of the cases can be plain or guilloched. The cases of many souscription watches have been replaced during the 19th century, probably scrapping the cold cases and replacing them with silver versions.

The movement: The watches are mostly huge, the movements have a diameter of 25 lines (56.5mm) whereas the watches have a diameter of 62.2mm. Some intermediate and small sized types exist as well. The souscription watch is very well suited to demonstrate the technical and aesthetic development of Breguet watches.

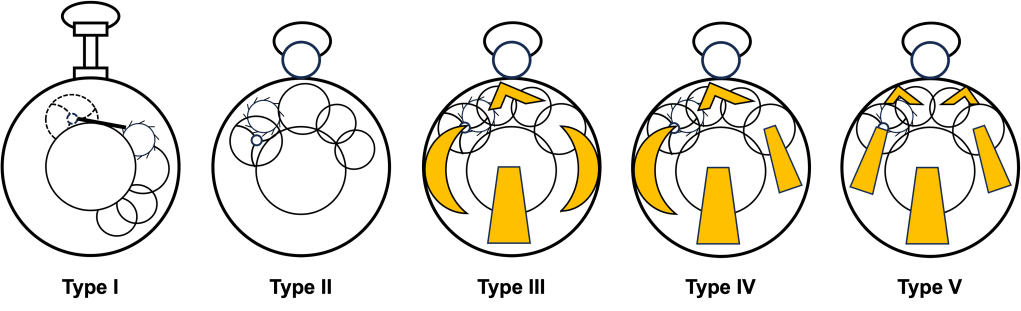

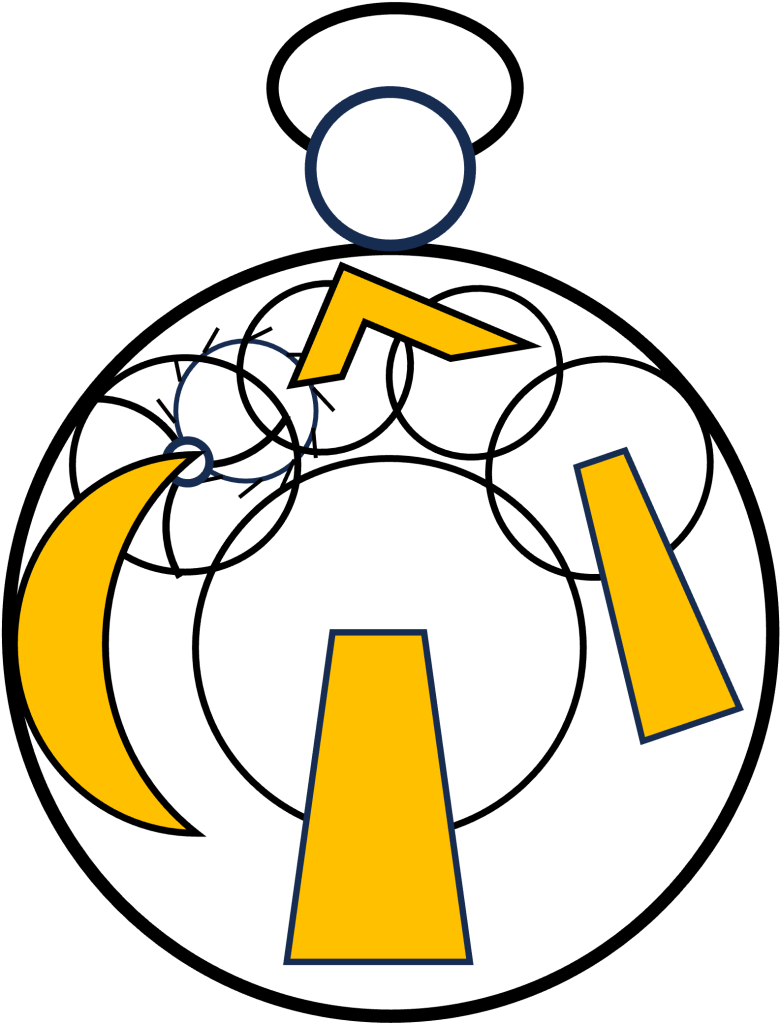

Five different types of souscription movements exist. The drawing above resumes the development of the movement of this model. There are basically 2 experimental types and 2 intermediate types before the final version is developed. The final version will then be the base for the development of the ‘montre é tact’.

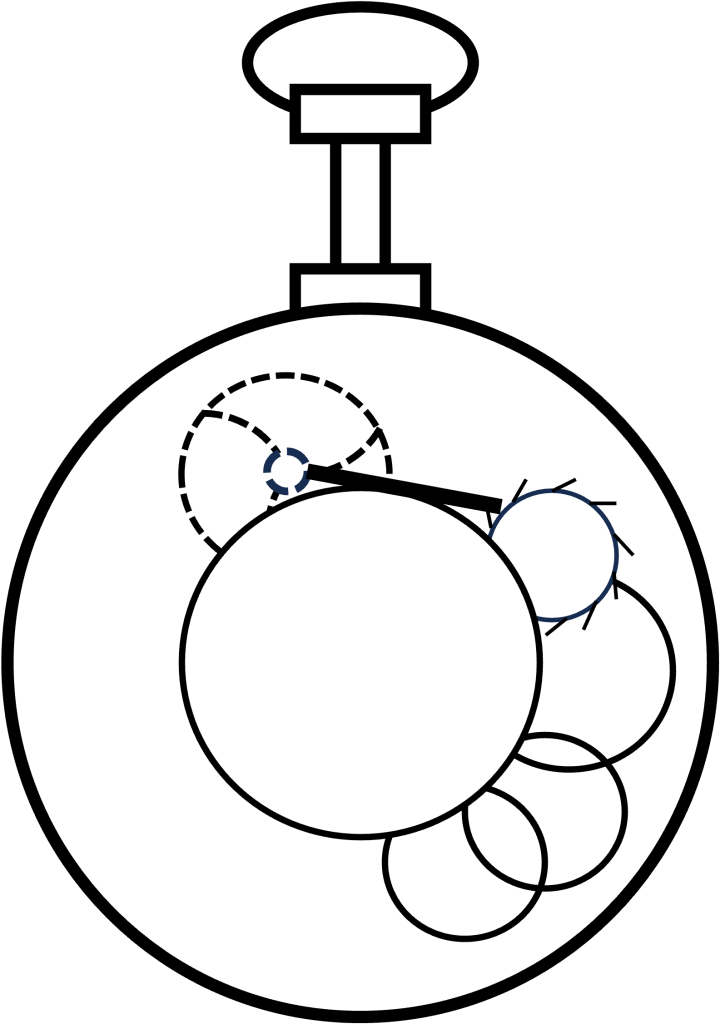

Type I - First Experimental version, 1791

The earliest version can be considered the prototype of Breguet’s souscription watch and features an experimental movement (first experimental version), which shows a two plate construction with a smaller, concentric back plate. These first experimental versions retain much of Jacques – Frédéric Houriet’s design, placing the wheel work around a big barrel, with the difference of placing the balance underneath the dial to keep the overall construction very thin. The main feature in Breguet’s version, the huge centrally located barrel (diameter: 25mm) is hidden, all the wheels are located around it on one side. These very rare versions (4 are known) have not the ruby cylinder escapement which is used later and their balance wheel is located underneath the dial. The watch is wound through the front, the winding square being inside the attachment for the hand. These versions were started as soon as 1791, even if it is often stated that Breguet invented this watch type while in exile in Switzerland. Some watches of this type are sold shortly after the return of Breguet in Paris in 1795. The back plates of these versions are not signed. If available, the signature and numbering is on the rim. The production numbers for these watches are from 96 up to about 350 (3rd series). The numbering of these experimental versions overlaps with the next generation of experimental movements and the first intermediate type. This fact suggests that both experimental versions and the first intermediate type have been refined at the same time.

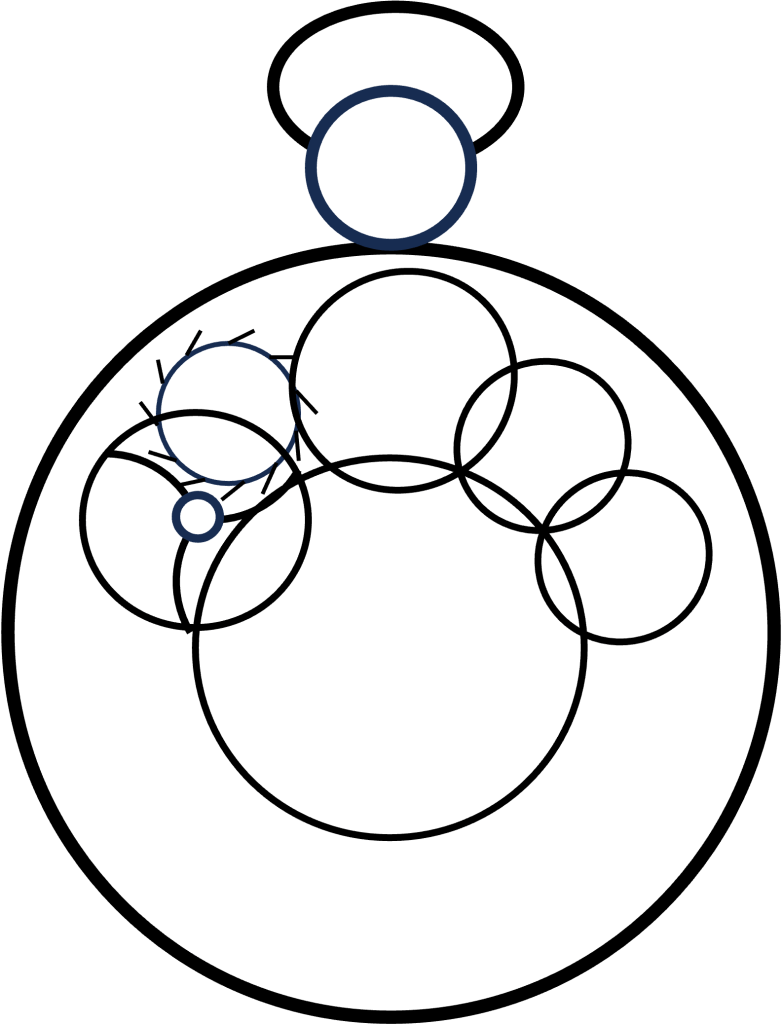

Type II – Second Experimental version, 1793

The second experimental version before the final ‘Lépine’ construction, is also of full plate configuration, but mostly features an overhanging ruby cylinder escapement as all later versions and has the balance spring on the underside of the watch instead of being underneath the dial (No. 324: Breguet Museum, Paris, No. 267/2267: British Museum, 1927,0513.2; No. 258: sold the 11.08.1799 to Monsieur Maleszewki, sold at Antiquorum, Geneva, 14.04.1991). The watch is wound through the front, the winding square being inside the attachment for the hand. Placing the balance on the underside of the movement makes it easier to overhaul. Because this movement type does still not show the definitive three bridge ‘Lépine’ aspect, it is also considered an experimental version. The back plate is normally signed and numbered. The production numbers for this version are approximately from 250 up to 350 (3rd series).

There is one version of this type numbered #15 which has been described to be an even more primitive version than ‘Type I’ and identified as the prototype of the souscription watches. However, this attribution has been made only taking in to consideration the small production number. If analysed the watch in its entirety, it is clear that it is a variant of ‘Type II’ with a triangular back plate instead of a round one and the small production number, certainly belonging to the 3rd series, would date the movement not earlier than 1793. To further sustain the attribution to ‘Type II’ is the fact, that the balance wheel is placed on the back side and not on the dial side as in ‘Type I’, which is a sign of a later development as this position of the balance wheel will be kept up to the definitive marketed version (Type V).

Type III – First Intermediate version, 1793 – 1794

The first intermediate version starts to show the three armed aspect and can thus be considered of ‘Lépine’ configuration, to the contrary of Types I and II, which are of ‘full plate’ construction. The central barrel is visible and held by a straight bridge. The back plate is gone. The other bridges are curved. This version has already been copied by contemporary watchmakers in order to share the market with Breguet. Of course the quality of the concurrence is not as good. The watch is wound through the front, the winding square being inside the attachment for the hand. No signature, or signature and numbering are placed on the plate between the bridges, the additional bridge (optional and maybe not by Breguet) stabilising the barrel, as seen in one example, partially covers the number. The production numbers for these versions are about from 200 to about 420 (3rd series).

Type IV – Second Intermediate version, 1794 – 1795

In the second intermediate, ‘Lépine’ version the lateral bridges are more straight, just the bridge holding the balance keeps a curved aspect. The bridge holding the barrel is broader and sturdier. The third and fourth wheels are still held by one bridge, as in ‘Type III’, which is now straight as well. The watch is wound through the front, the winding square being inside the attachment for the hand. The signature and numbering on the plate between the bridges gets more symmetrical, but the orientation of signature and numbering is not the same. The production numbers for these versions are about from 400 to 500 (3rd series).

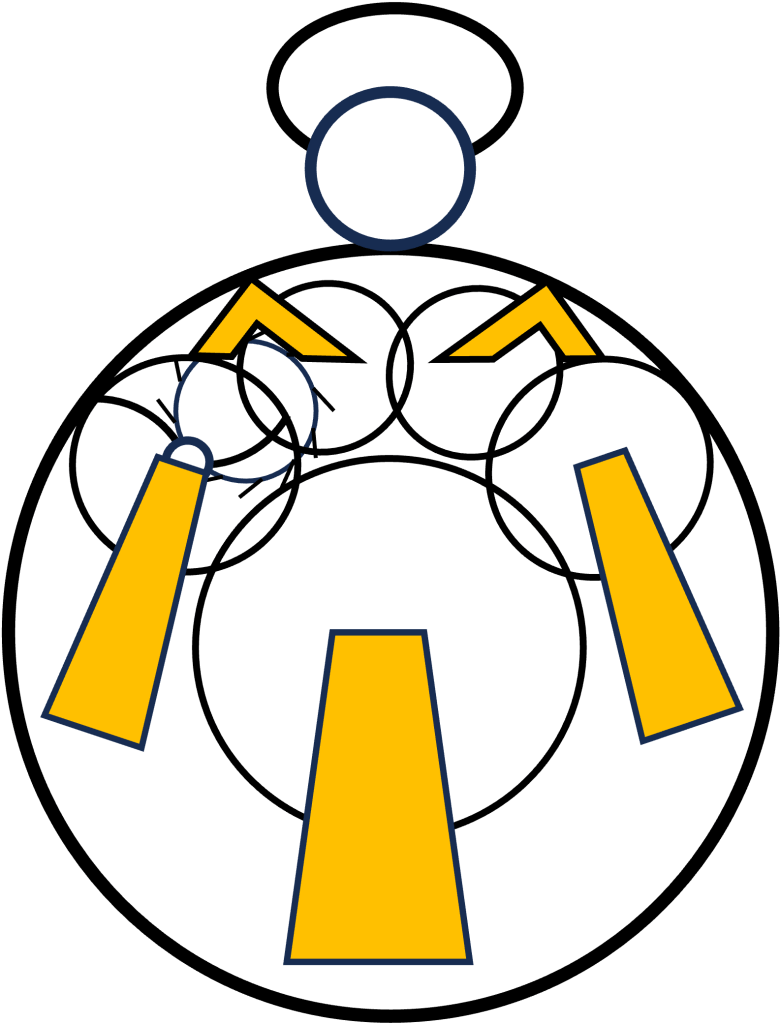

Type V – Final version, 1796

The final version is of course the most common one. It represents also the version pictured and described on Breguet’s patent for the ‘Montre Souscription’ of 1796.

Of ‘Lépine’ configuration, the bridges are straight, the third and fourth wheels are held by two symmetrically positioned bridges, in later later versions both wheels are held by one central bridge. Overall the movement has attained the most harmonious and symmetrical aspect of all versions. The signature and the numbering are placed on the plate between the bridges and are highly symmetrical. The watch can be wound from the front and the back to the contrary of all other versions. The orientation of signature and numbering is the same. The production numbers for these versions are about from 500 to 4300 (3rd series) and are sold way past the death of Abraham – Louis Breguet in 1823. This version was also the base for the development of the ‘montre à tact’ and the design for the ‘montre simple, nouveau calibre’.

Type VI – ‘Montre à Tact’, 1799

The ‘montre à tact’ or ‘tactile watch’ is an ingenious invention by Breguet made in 1799. Without the need of reinventing much of the movement arrangement, just by transferring the wheel work onto an arbor on the back side of the movement he could have the main arbor activate a big hand on the outside of the case and the auxiliary arbor acting on normal hands on a smaller dial. The smaller dial can also lack. The rotation of the big hand can be felt in ones pocket and compared to protruding indicators on the rim of the case, for the most luxurious models made of big diamonds or pearls. This way it is possible to estimate the time quite precisely without the need of getting the watch out of the pocket or to rely on potentially disturbing chimes of a repeating watch.